Questioning Sex Essentialism As Feminist Practice: An Interview With Janis Walworth

Pt. 2,The Sex/Gender Binary: Essentialism

November 30, 2015Pt. 3, To Question Sex Pedagogy

January 23, 2016Janis Walworth, a radical lesbian activist and progenitor of the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival (MichFest) protest that came to be known as Camp Trans, speaks about the structural practice of sex essentialism within a community constructed to be a feminist safe space. Walworth recounts the incidents leading up to the establishment of Camp Trans as well as her research revealing that a majority of MichFest attendees were welcoming of trans women.

Keywords: SOCIAL CONSTRUCTIONISM Lesbian Feminism Sex Gender

Questioning Sex Essentialism As Feminist Practice: An Interview With Janis Walworth

BY Cristan Williams

@cristanwilliams

The Background

In the middle of a cool August night in 1991, Nancy Burkholder was expelled from the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival (MichFest) because she was an admitted trans woman. Burkholder’s friend, Janis Walworth –a cisgender radical Lesbian feminist– became outraged that MichFest would engage in anti-trans discrimination. In response, Walworth immediately began educating MichFest attendees about trans people. After coping with threats of violence and dealing with having her consciousness-raising space vandalized, she –with body guard protection from the Lesbian Avengers– helped form what became known as Camp Trans.

She told that I had I had to leave the festival and that I would not even be allowed to return to my campsite to retrieve my equipment. I realized that Chris and Del were expelling me in spite of all the irrefutable legal and anatomical proof that I was a women. I knew there was nothing more I could say to these women. I resigned myself to the fact that these women were expelling me from the festival. – Nancy Burkholder, 1991

Camp Trans consisted of several dozen transsexual women and supporters who leafleted MichFest attendees, held workshops and readings that attracted hundreds of MichFest women. The significance of this protest was noted by trans and intersex activist Riki Wilchins who wrote, “… it was the first time that significant numbers of the hard-core lesbian feminist community backed us”1

Cristan Williams: I understand that you were very active in the first response to the trans-exclusionary policy at MichFest. Can you talk about that?

Janis Walworth: From what I understand, MichFest had a trans exclusion policy before Nancy [Burkholder] was thrown out of the festival, that this policy had been discussed quite some time before, like in the late 1970s.

Williams: Ah, yes. Lisa Vogel – the owner of MichFest – and several MichFest acts were active in the effort to put pressure on Olivia Records, a radical feminist Lesbian-separatist music collective, for being trans-inclusive in the late 1970s. All of that culminated in armed sex essentialist women asserting their desire to murder Sand Stone, the trans woman who was a member of the Olivia Collective. There’s a newspaper from 1977 that published an open letter to the Olivia collective that Lisa Vogel signed onto, condemning Olivia’s trans-inclusive policies. I can understand how that anti-trans ideology was there in the early days of MichFest.

Excerpts from Vogel’s letter to Olivia

Dear Olivia:

We are writing concerning your decision to employ Sandy Stone as your recording engineer and sound technician. We feel that it was and is irresponsible of you to have presented this person as a woman to the women’s community when in fact he is a post-operative transsexual.

Given the narrow options available to us, it is also likely that many of us would have to work with Stone. Some of us have already done so without the knowledge that this person was not a woman. When we did discover the truth about Stone and tried to discuss this with you, we were told that you considered him very much a woman, a lesbian, and that you trusted him more than middle class, heterosexual women. This was very painful to hear and indicated a great lack of respect and love for women and our struggle. We do not believe that a man without a penis is a woman any more than we would accept a white woman with dyed skin as a Black woman.

Fig 1: Open Letter to Olivia published in Sister, 1977 | Photo: Williams

Walworth: Yes, there apparently was a policy, which was never promulgated in any significant way. Although, the festival organizers apparently understood that the phrase “womyn-born-womyn” was meant to exclude trans women, other people didn’t necessarily understand the meaning the festival gave to that phrase.

Williams: So, after you heard about Nancy’s expulsion from the festival, what was your response to the festival’s behavior?

Walworth: I had been a friend of Nancy’s for a while before that. She and I had both gone to the festival in 1990 and there were no incidents. So, she had come there in 1991, I was there also, she had come with her friend. Laura and I had seen Nancy at the beginning of the festival, and then I didn’t see her again, for several days. I began to wonder — of course, there are so many people in there, it’s easy enough to not run into people — but, I had really been keeping an eye out for her and had not seen her. Finally, Laura found me and told me what had happened.

I then called Nancy and talked to her about it and we agreed that it was important for as many people as possible to know out this and I spent the rest of my time at that festival talking to people and just letting them know what had happened. And most people I talked to were horrified. I remember talking to one person – someone that I had known personally for a long time – whose response was, “Well, that’s the way that it should be.” So, there was a range of responses, but really, most people I talked to were like, “REALLY?!? That’s unbelievable!”

So, that was the initial response to what had happened. It was in 1991 when Nancy was thrown out. We were just all in shock about it and we were just trying to let as many people as possible know about what happened.

After the festival, we began a letter-writing campaign, writing gay newspapers and stuff like that, just to make sure that people knew.

Williams: So, when the 1992 festival rolled around, were you involved in any of the actions that happened that year?

The Beginning of Organized Resistance

Walworth: Oh yeah. Yes. In 1992 it was decided that – I mean, I had been talking with Nancy and with some other trans activists – we decided that somebody needed to go back to the festival and let people know what was going on and to make our voices heard so that we could start doing some education.

So, I went back there and I went there with Davina Gabriel, my sister went with me, another woman named Brandy and another woman from Kansas City. So, the four of us went and we had a lot of literature. I had written up what I called, Gender Myths – they were just a short statement of some belief some people held about trans women and men and then under that, the Fact, a little paragraph explaining what was factual – and we had these printed up in bright colors and we posted those in the port-o-potties. We went around every day, with handfuls of these things. I mean, a lot of people put literature in the port-o-potties because, while you’re sitting there, it’s something to read. So, we posted these Gender Myths in ALL the port-o-potties. They got torn down on a regular basis, and so we went around, every single day, and posted them again, sometimes twice a day.

We also had a table out at the area called One World, which is the area for literature, and they have tables set up there so that people can put up literature there. People usually just put literature out and walk away. We actually took a table and brought some chairs and sat behind it and talked to people as they went by, which was kind of unheard of in that area, at the time.

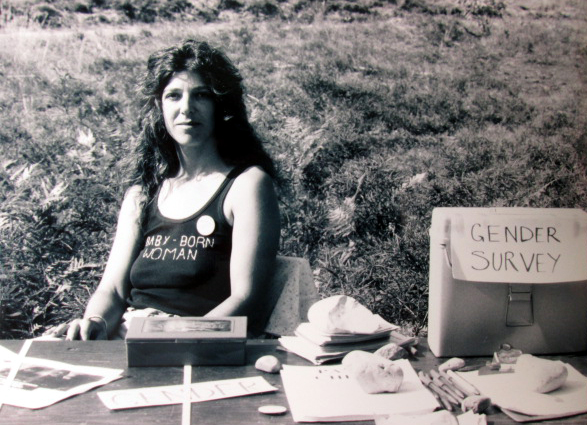

We had buttons made up like “Friend of Nancy” and you know, a lot of people took these buttons and wore them around. One of the biggest things we did that year was a survey because I wanted to find out exactly how much support we had.

Williams: WOW! I’ve never heard of this survey before!

Walworth: Yeah, it was a really important thing for us to do because I felt like we could sit there and hand out literature all day, but we didn’t really have any basis for doing a real protest without knowing what our support-base was.

The 1992 Trans-Inclusive MichFest Survey

Gender Opinion Survey:

- Do you think that male-to-female transsexuals should be welcome at the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival (MWMF)?

Circle one: YES NO

Why or why not? ________________________________________________ - If not, what would be the best way to determine if a person is a male-to-female transsexual?

_________________________________________________________________ - Do you think that female-to-male transsexuals should be welcome at the MWMF?

Circle one: YES NO

Why or why not? ________________________________________________ - If not, what would be the best way to determine if a person is a female-to-male transsexual?

____________________________________________________________________

Use the back of this paper to tell any personal experiences you have had or beliefs and philosophies you hold that contribute to your views about this topic.

Thank you!

Walworth: We had a box at our table so that when they got done with the survey, they could drop it into the box. Every night we took the survey all the way back out to my car and locked them in the car because we were afraid that somebody would vandalize them if we left them out. Other tables had surveys that were left out so that people could just do them around the clock, but we were afraid that if we left them unattended, something would happen to them.

I have the results. We did a total of 633 surveys and there were about 7,500 attendees that year which gave us a response rate of 8.4%. The margin of error was 3.8%. We did this right [laughs].

In answer to the first question, YES responses were 73.1%; NO responses were 22.6% and the other 4.3% were things like, “I’m not sure” or simply did not answer.

Given these results, the chance that the majority of 7500 MichFest participants believe transsexuals should not be admitted would be less than 1 in 100,000. This calculation assumes that our sample was randomly selected, which it certainly was not. However, even if half of the YES answers are attributed to the bias of the sample and eliminated from the calculation, there is still a better than 999 in 1000 chance that most Festigoers would welcome transsexuals.

The reasons Festigoers gave for wanting to exclude transsexuals were:

- They are not women

- They are not women-born women

- They make others uncomfortable

- They have been socialized as males

- They have had male privilege

- They think like men

- They have male energy

- They have penises

- They behave like men

- They are too feminine

Reasons given for including transsexuals were:

- They are women

- They identify as women

- They have made a commitment to womanhood

- They have been through enough

- We should not oppress others

- They have chosen to be women

- We should be inclusive

- We should not judge an individual’s choice

- They can benefit from the women’s community

- Internally they are women

- They are oppressed as women

- They are living as women

- They share women’s goals and perspectives

- They are not threatening

In answer to the question, “What is the best way to determine whether an individual is a male-to-female transsexual?” there was a considerable range of opinion. Of the 227 responses, 126 were from those against inclusion, 86 from those women in favor of inclusion and 15 from those without a clear opinion about inclusion. And here are the reasons that people gave:

- Ask them

- Trust them to be honest

- Don’t know

- Announce the policy clearly

- Check their genitals

- There is no accurate way to tell

- Driver’s license or picture ID

- There is no dignified way to tell

- Self-identification should be sufficient

- We shouldn’t try

- Surgery should be complete

- By their behavior

- Genetic testing, [laughs] I love that one! Do these people think we are going to do genetic testing in the woods?

- Birth certificate

- Written exam or questionnaire

- Medical certificate

Of course, these people are not thinking about the fact that, in order for this to work, everybody has to bring this documentation! They’re just thinking that stuff like this would only apply to trans women when, in fact, everybody would have to do this!

Cristan: [Laughs] Genital checks and genetic testing! [Laughs]

Walworth: [Laughs] Additionally, two were in favor of interviews, having a friend vouch for them and “intuition.”

Cristan: [Laughs]

Walworth: [Laughs] I guess they were thinking that there would be psychics posted at the gate entrance.

Cristan: And this was in 1992, right?

Walworth: Yes, yes. Another response was that everyone should have their testosterone levels checked and that everyone’s bone structure should be scrutinized.

Cristan: [Laughs] Wow!

Walworth: So there you go!

Trans Camp: 1993

Cristan: So in 1992, that was where the momentum for Camp Trans began?

Walworth: That first year, 1992, we did the survey with the intention of continuing on with some kind of protest or engagement with the festival. So yes, this was the groundwork. This was the beginning. We spent our time at the table doing education with the Gender Myths and doing the survey to figure out what our support base was like.

We also had an engagement with Alix Dobkin that year.

Cristan: Oh? Alix was one of the sex essentialists who signed onto that horrible open letter to Olivia, attacking Sandy Stone.

Walworth: Yes, she is very anti-trans. She came to do a community forum and her workshop area had like, more than 100 people. It was just an opportunity for people to ask questions and she would answer them. And so, I went there and I was wearing a shirt that Anne Ogborn had given me. She wasn’t able to be there, so I wore the shirt she had given me and the shirt read, in these huge letters: SEX CHANGE.

Cristan: [Laughs]

Walworth: And so I went to Alix Dobkin’s workshop wearing Anne’s t-shirt. Alix did her thing and people would ask questions and, it’s not like she knew the names of anyone who she was calling on to ask her a question, so she would call on people by saying things like, “You with the curly hair and sunglasses.” When it came time for me to ask a question, Alix pointed at me and said, “Yes, you – sex change.”

Cristan: [Laughs]

Walworth: One of the things she was talking about was how she was tired of people whining about how things aren’t the way they wanted and if people wanted to change things about the festival, they should come here and engage in dialogue. So, when she called on me, I asked, “How can people show up when they are not allowed through the front gate?” To which she didn’t have a response.

She came by our table and we asked her to fill out a survey. She was [pause], she was not friendly toward us. I mean, we wanted to dialogue with people and so we were always very civil.

In 1993, we went back again. There were four trans women and me in 93. We were prepared to be thrown out. We again set up a table, like we had before and we proceeded to do our educational outreach.

Some people in the festival began harassing us and then around noon on Wednesday or Thursday, the festival security stopped by and told us that the trans women in our group would have to leave, “for their own safety.”

Cristan: For your own SAFETY? Are you saying that sex essentialists were talking about attacking your group?

Walworth: Tensions were definitely rising, we were told. We had scheduled to do some workshops and some folks were definitely hostile. We were told that, for our own safety, the trans women would need to leave the festival as soon as possible. It was a situation.

We had decided before all of this that if they asked us to leave, we would leave. We had all of our camping gear and had decided that we would just set up across the street from the festival.

We decided that I would stay inside the festival to continue educating people and the other folks would set up camp across the street from the festival in protest.

They made very slow progress out of the festival because people kept stopping them and asking why they were leaving and then they would explain the whole thing – which was a great educational moment – but the leather Dykes had stopped them.

The leather Dykes were trying to convince our folks to not leave the festival. They said that they would provide body guard protection for our group, in their camp. They were very adamant that the threatened violence was wrong, that forcing the victims of the threatened violence to leave was wrong, and that the entire policy was wrong.

Ultimately, we stuck to our plan and we set camp for the trans folk.

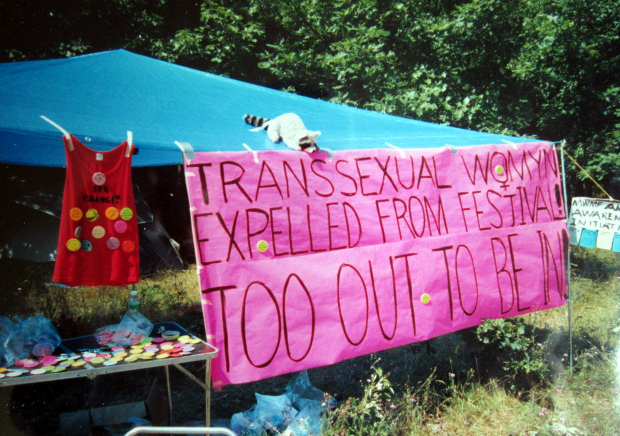

The next day, I made sure our education table was set up, and then went to visit the Camp. They had put up an amazing sign. It was a bright neon pink banner and on it was written in big letters, “Transsexual Womyn Expelled From Festival: Too Out To Be In!”

Fig 7: “Transsexual Womyn Expelled from Festival! Too Out To Be In!” First Trans Camp, 1993 | Photo: Walworth

There was no way that you couldn’t see the banner, coming or going from the festival. They had set up a tarp and a table with all of our literature there. That space became a really cool thing because you could not miss this camp. Every woman who left the festival or who came back into the festival saw this sign.

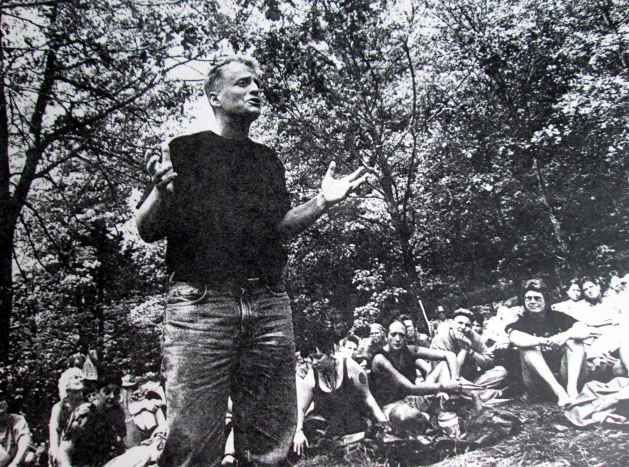

People wanted to know what was going on. A lot of people stopped and talked with us out there. People came out from the festival to specifically talk with us. We had workshops that were scheduled inside the festival, so we posted that they would be happening outside the festival, and people came out of the festival to attend our workshop.

People came out and they brought food, and water, and flowers, I mean, it was an amazing, amazing thing.

I spent time going back and forth between the Camp and our table inside, because I was the only one who could do anything inside. Our table, inside the festival, was vandalized while I was at the Camp. They had taken our stuff from our table – buttons, literature, supplies — and dumped it into a port-o-potty. I informed security because it was going to cause a problem when it came time to clean it out.

I started putting out only a few things while I was gone so that when it would be vandalized, we would still have some things to put out afterwards. The literature that we put up, was torn down routinely.

Camp Trans: 1994

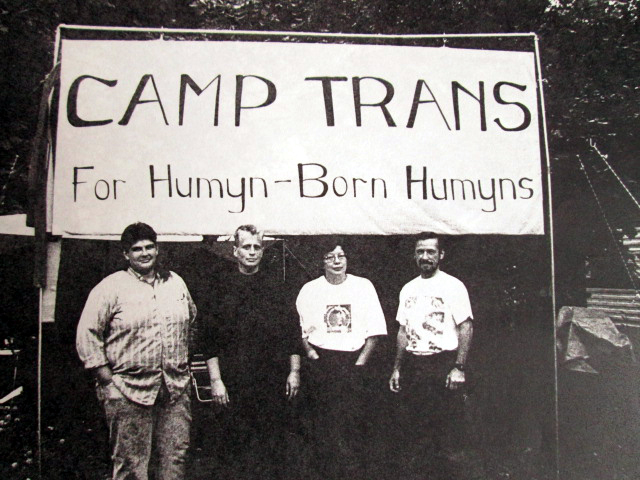

Camp Trans really came into focus in 1994. We had a year to organize and let people know where we were going to be. Riki Wilchins had shown up at the end of the 1993 Camp and she really became involved in 1994. I think she was the one who thought up the name, “Camp Trans.”

That year we went back with the intention of not going back into the festival because we could do our work outside the festival. We were WAY more visible across the road. For that festival, we made a banner that said, “Camp Trans: For Humyns-Born-Humyns.” There were 28 people who came to camp that year. There was Riki, who brought a lot of people from New York, Leslie Feinberg and Minnie Bruce Pratt, an intersex woman, an older grandmotherly woman, a friend of mine and her partner and their 4 year old and Nancy Burkholder was there again. So, we had the camp made up of all kinds of people, ages four to 70-something and every sort of gender you can think of.

Cristan: [Laughs] That’s awesome!

Walworth: As people were coming into the festival, we were handing out literature. The festival organizers didn’t like it. They were telling folks not to take our literature, the sheriff came out, and the park ranger came out. They would do things like wait until five in the morning when we were all asleep and blare loud music at us.

Cristan: Oh wow! So, the festival really worked to try and silence you.

Walworth: Yeah, but we kept doing our education. What we were doing was amazing, though. I mean, we had this lesbian couple come out to Camp Trans to get married. One of the trans women was a minister and this couple thought that the best place to have their wedding was at Camp Trans!

The grandmotherly woman went up to the festival gate to go into the festival because she knew that she had a friend inside that she wanted to see. Since she was over 65, she didn’t have to pay and so when she got up there, the security people at the gate knew that she was from Camp Trans. They debated over what to do and they finally allowed her to go in with a security detail, “for her own protection,” they said. She said, “Why do I need protection. I’m a grandmother. Are you saying that an old woman like me can’t go safely into your festival? What kind of place is this?”

Cristan: [Laughter] I can’t believe that she had to have protection! That’s horrible!

Walworth: There were a whole bunch of Lesbian Avengers inside the festival and they were going to have a workshop. Some of them had come out to our Camp and they wanted us to come to their workshop. We explained the safety situation with them and they said, “Well, what if we send out a bunch of Lesbian Avengers out to escort you in?” They were offering to guard us. Knowing that we would have them as guards, we thought that maybe we could do it. Some of the folks from our Camp felt like they would be okay going inside and so, we had this contingent who would go to the Lesbian Avengers meeting and then they would walk us out.

So, everyone from our Camp who self-identified as a womyn-born womyn decided to purchase a day ticket so they could go to the Lesbian Avengers meeting. We also had a training on how to deal with hostility, if anything happened. So, when the time came, a big group of Lesbian Avengers came out and met our group and they escorted our group to their meeting. The Lesbian Avengers came, they were beating drums and singing songs and welcomed our group into their own. They marched all the way to the meeting, they did the workshop and then, the Lesbian Avengers marched our contingent through the rest of the festival. So, all of this was highly visible. After the show of solidarity, the Lesbian Avengers marched back down to Camp Trans, safely returning our group to us.

Cristan: Wow! That’s, just amazing!

Walworth: Yes, it really was. The Camp Trans experience was a beautiful thing and the support that so many of the festival goers was just fantastic!

A version of this article first appeared on the TransAdvocate.